If you know me personally, you also know that I have been working to support migrant families and communities for most of my adult life. This work springs from now over two decades of close relationships with Salvadoran families, whose lives have all been profoundly shaped by migration.

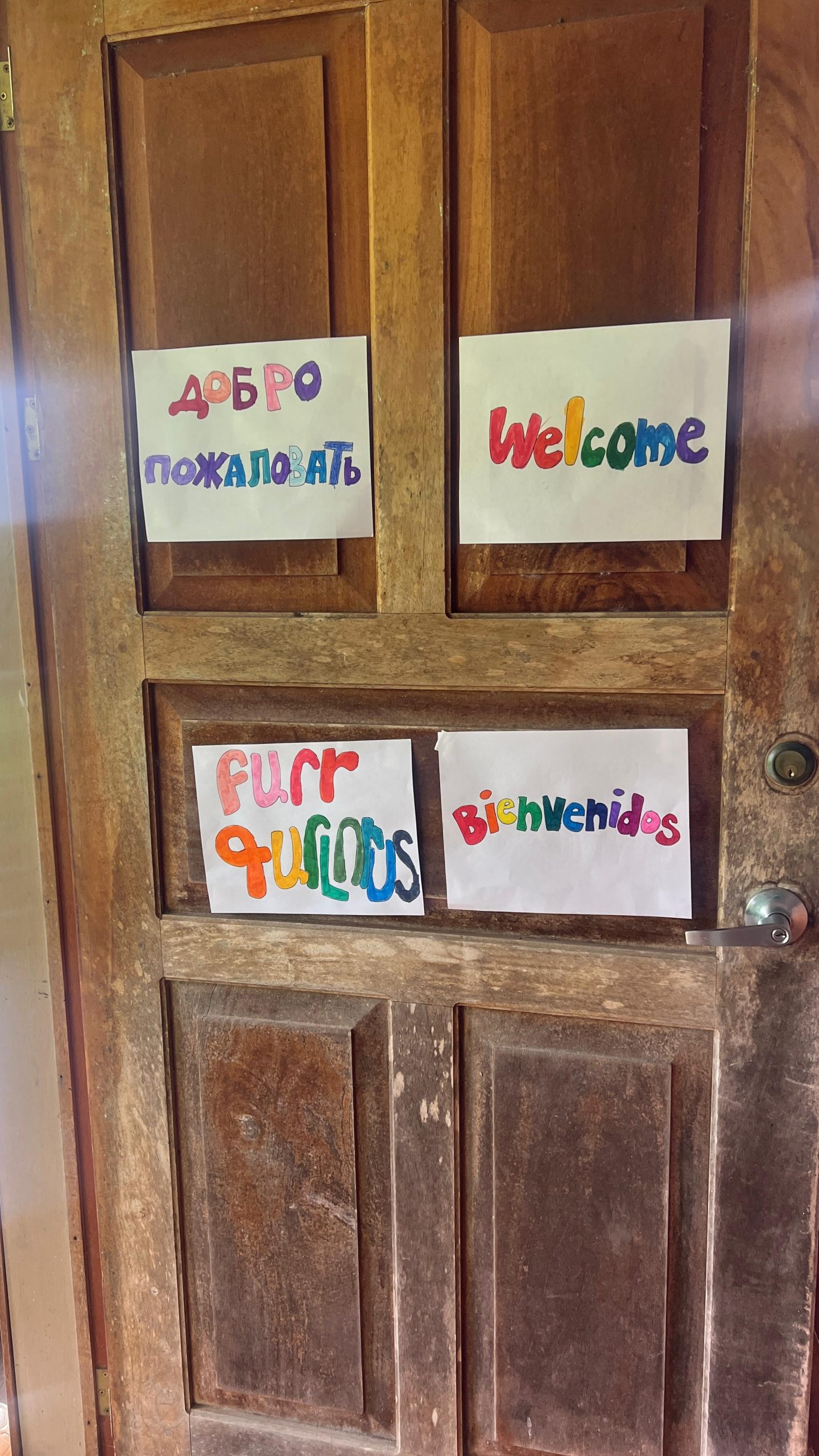

I am always inspired when I meet others who share this concern for migrant communities, and I have been fortunate to connect here in Monteverde with an amazing project called Proyecto Bienvenidos (Welcome Project). Since July of this year, this small group has been working to support several families from Eastern Europe and the Caucasus who ended up here in Costa Rica after trying to seek asylum in the United States.

To learn more about who these families are, how they ended up in Costa Rica, and what their experience here has been like, I invite you to read this article that I wrote for Friends’ Journal (a prominent Quaker magazine). In this post, I want to take the time to share a more personal reflection about this experience.

When we arrived here in early August, the migrant families had also only just come to Monteverde. The Quaker Meeting that we attend was holding fundraisers almost every week to gather the funds needed to continue to meet the basic needs of the families, whom they had agreed to help for up to a year. Most of the families were living in houses or apartments loaned to them by members of the community, but we still needed to raise funds for weekly food stipends, for transportation to and from schools for these families, as well as for medical needs and other expenses.

So on August 30, our third Saturday in the country, we opened our house to some of the families to help them prepare for a fundraiser lunch the following day. I spent the day cooking with two young mothers, one from Armenia and one from Russia, while Pat kept their children (and Sophie) entertained and occupied.

For me, it was quite an experience, working together intensely for 11 hours and getting to know each other while navigating some complicated language barriers. One of the women spoke Russian and pretty good English; the other spoke Armenian, some Russian, and limited English. So it was often like a game of telephone to communicate with each other! Still, they were really good at showing me what I could do to help them: I chopped a lot of vegetables and washed a lot of dishes!

We listened to Armenian music and there was a lot of laughter and singing and dancing in between the cooking. By the time the day was done, we were all exhausted, but I felt I had started to build two new friendships. The next day, we helped the families take the food up to the Meeting House and set up to sell lunches. We had spread the word in the community and a big crowd turned out to try the delicious dishes and help support the families.

In the months since then, we have celebrated children’s birthdays with the families, held a fun Coffee House (talent show) fundraiser with tons of amazing acts and delicious food, and written thank you letters to donors. But for me the most powerful experiences have been ones like that day of cooking when we are able to spend time together. We’ve invited families over to our house regularly for dinner and games, always an interesting time as we learn how to communicate despite the language barriers.

Now several months into their stay in Monteverde, the situation has evolved. Some of the families have decided to stay in the area, at least for a while, and have begun to find work and improve their Spanish skills—none of them spoke Spanish at all when they arrived, since they had never planned to move to Costa Rica. Patrick worked with one family to make a bilingual (English/Spanish) flier advertising their hair cutting services to try to help them find more clients.

Some families, however, made the painful decision to leave Costa Rica and try again to enter the United States. All of them had loved ones there—often their spouses and other children—who they longed to be reunited with. The pull to be together as a family ultimately outweighed the risks of the journey, which they knew all too well.

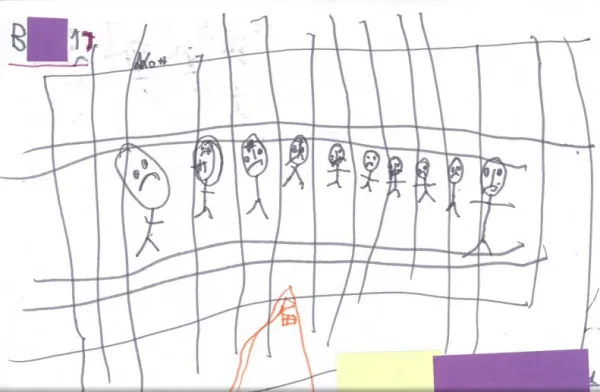

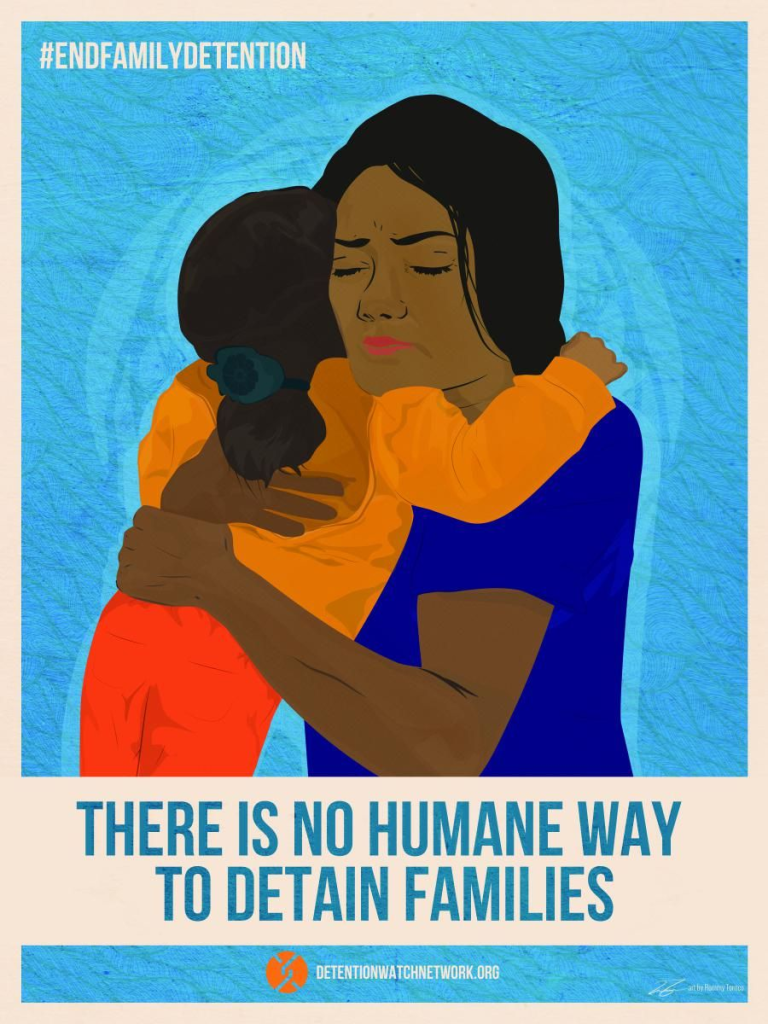

As I write, three of the families that we met are being held in an immigrant detention center (a jail) in the United States. One of them is one of the women I got to know during the day we spent cooking together. My heart breaks every time I think of her, her children, the other families we met, and all the many immigrants we don’t know who like her are being held indefinitely in these prisons, most of which are run by big corporations (GEO group and Core Civic) who are making money off of locking up parents and children.

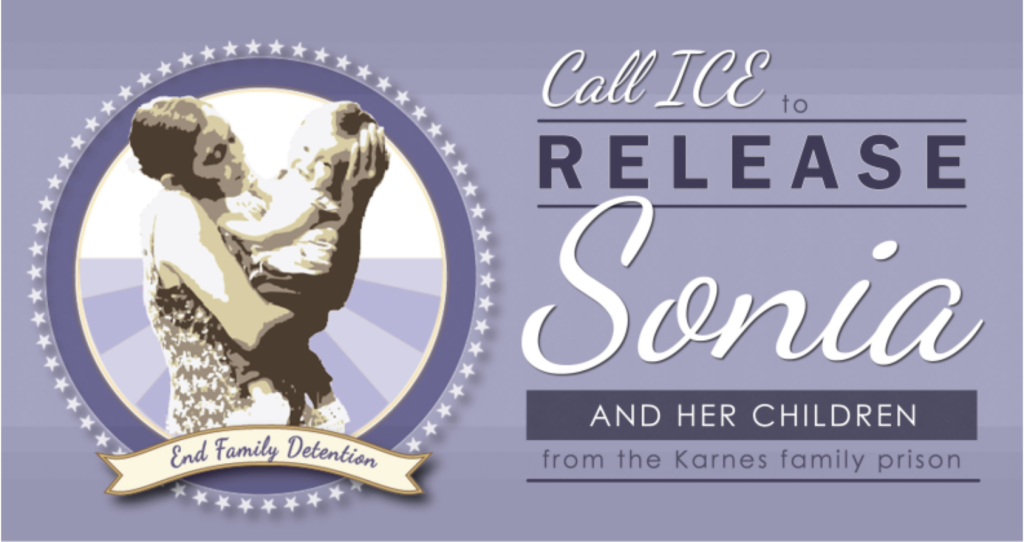

This feeling of heartbreak resonates deeply for me. In 2014-2015, a close friend of mine from El Salvador was sent to a detention center with her three small children by the Obama administration. Like the families I met here in Monteverde, she was fleeing an unsafe living situation in El Salvador and trying to reunite with her husband—the father of her children—in the United States.

I will never forget what it was like to visit her at the detention center in Texas where she was being held. I had to empty my pockets and walk through a metal detector and multiple locked doors. On the other side of the locks there were young children and traumatized mothers. I didn’t have a child myself at that time, but now as a mother, I cannot imagine what it is like to see your children locked up and deprived of the freedom they need to thrive.

Many of the detained immigrant mothers were desperate to call attention to their situation and they decided to organize a hunger strike. Allies and community members outside of the detention centers organized alongside them, and I participated in a major protest they organized in May 2015 outside of a new family detention center that was being built in Dilley, TX.

As a result of this pressure and ongoing legal campaigns, court rulings were handed down in 2015 and 2016 that reinforced earlier decisions that had made the long-term detention of children illegal. My friend was finally released after 9 months in detention. Her youngest son, who had just turned 3 when she was released, had spent a third of his life in jail.

Sadly, the Karnes and Dilley detention centers never shut down entirely. After holding only adult immigrants from 2021-2024, the Trump administration re-opened them as family detention centers. The families that we met in Monteverde are most likely being held at one of these two centers, which together can hold 3,500 people. The funding bill passed in July of this year contains $45 billion to build more immigrant detention centers, including new prisons for families. This recent news stories contains accounts from families about the horrific conditions they face at these detention centers.

At this time of year when many of us are fortunate to travel to be with our loved ones, please remember these families who have been locked up simply because they wanted to be together, in safety, with their loved ones.

If you feel called to take action, here are some things you can do:

- Contact your elected representatives and ask them to end family detention now.

- Support the work of Proyecto Bienvenidos by sending an earmarked donation to Monteverde Friends U.S.

- Support the work of organizations fighting to end family detention, including: The Children’s Defense Fund, Tsuru for Solidarity, RAICES, American Friends Service Committee, Grassroots Leadership, and the National Immigration Project.

- Connect with a group in your local area that is working to support immigrants. There is so much important work to be done!

Leave a Reply