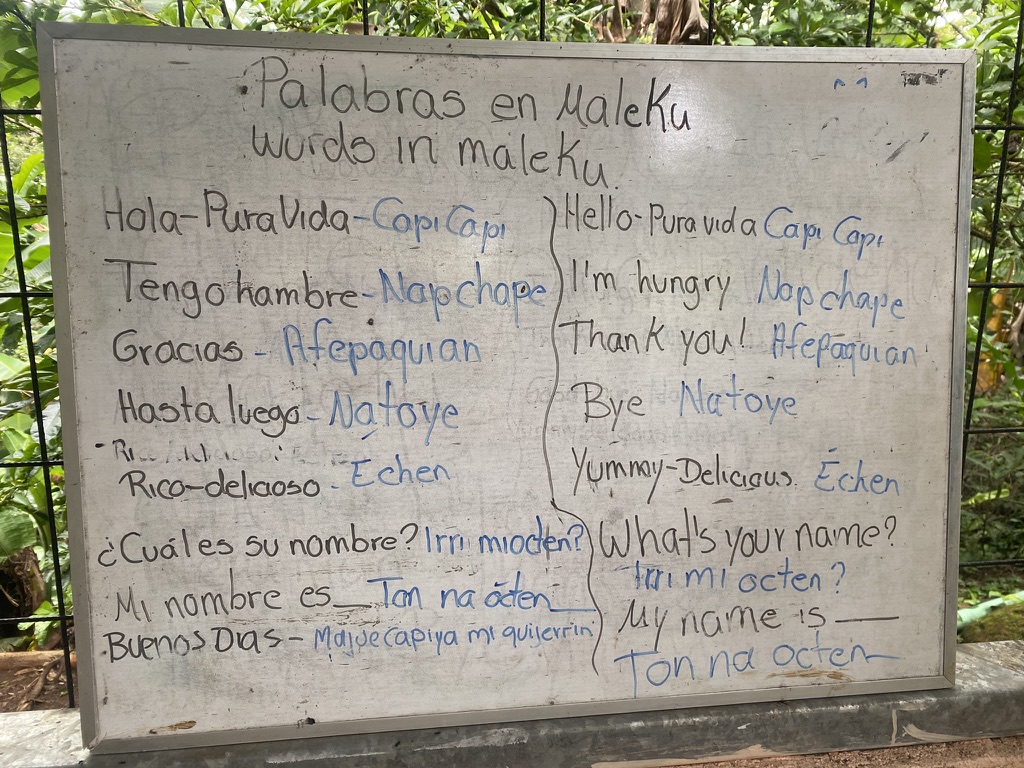

Costa Rican Spanish has some unique characteristics. You’ll hear about the phrase pura vida as soon as you walk off the plane, for instance. It means something like “pure life”, literally, but it really means something akin to “aloha” in Hawaii: hello, goodbye, thank you, etc., etc. People say it all the time.

Lynnette’s favorite is ¡que dicha! which translates as something like “what luck” or “luckily”. When something nice happens you often hear people say que dicha.

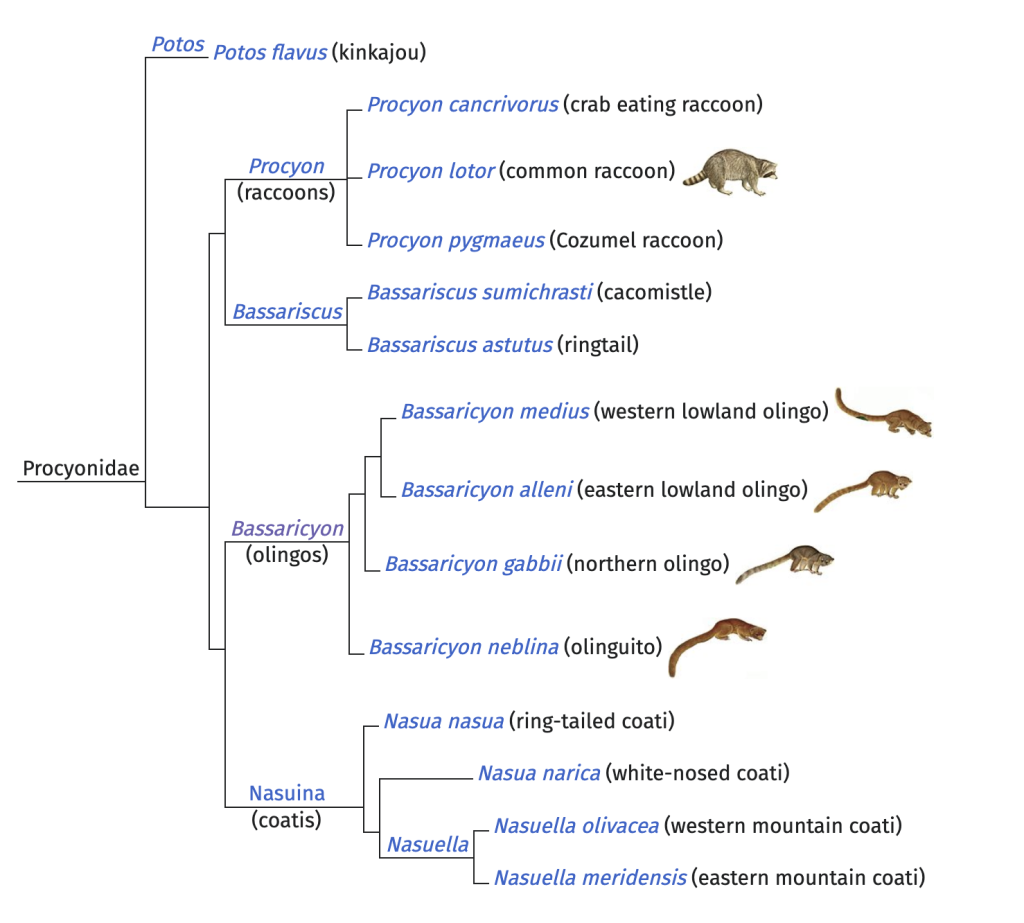

And then, of course, there are local vocabulary words that are just different here. In some parts of Costa Rica, an agouti is called a cherenga, but it’s also known as a guatusa.

But every country has its special vocabulary. What I find more interesting is the fact that Costa Rica has some distinct grammar, and what’s more, that grammar is in a state of flux.

When one is taught Spanish in the United States, you usually learn a variant which is close to (for example) the Spanish of Mexico or Puerto Rica. In such variants, there are two ways to say ‘you’, tú and usted (which is usually abbreviated Ud.).

When you use usted, you may mean ‘you’, but grammatically speaking you’re saying “he” or “she”—in grammatical terms, it’s the third person. It’s a bit like how one might address a king or a queen with “your highness” or a judge as “your honor” in English.

Nowadays, in Mexican Spanish, usted is not as fancypants as “your highness”, but it the more respectful choice—you use it when you’re talking to an older person, or a teacher, or to someone in a business situation. Tú is less formal—you use it when you’re talking to children or friends. So to summarize:

There are two ways to say “you” in Mexico or Puerto Rico

| Person | Formality | |

| tú | Second | Informal |

| Ud. (usted) | Third (Second meaning) | Formal |

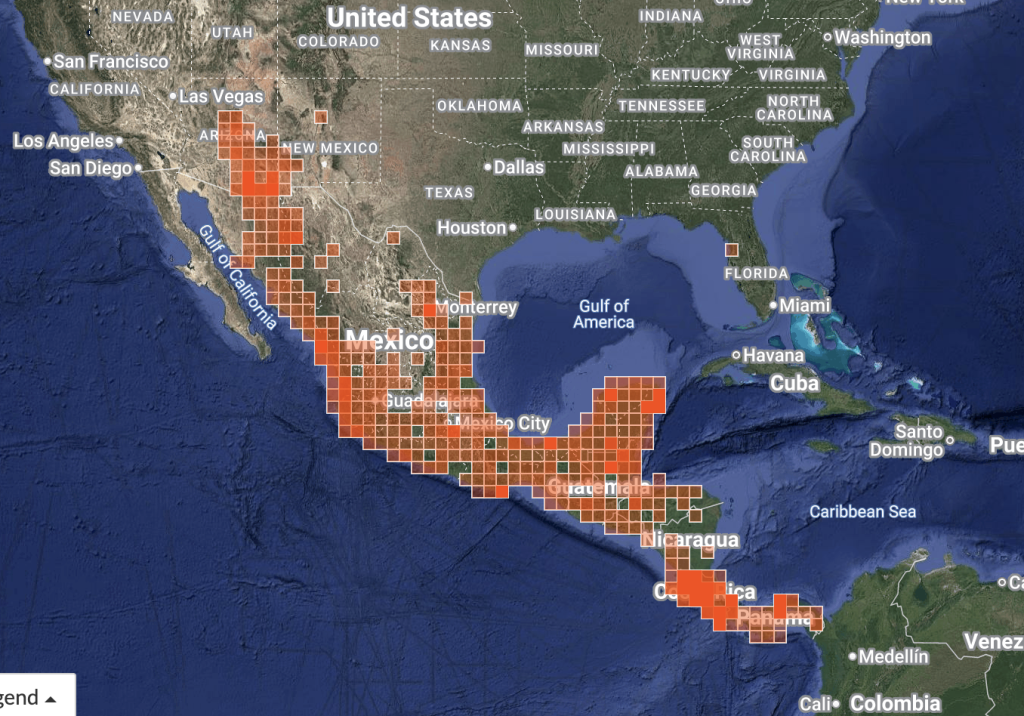

This pattern is called tuteo in Spanish linguistics, and is the standard in lots of countries. In the map below, the dark gray countries all use tú for informal contexts and Ud. in formal contexts.

Three ways to say ‘you’

So what about the blue bits? Well, that’s where things get more complicated. In Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, El Salvador, and to some extent in Bolivia and Chile (and some parts of several other countries) there’s a third way to say “you”: the pronoun vos. The details of how second person pronouns work in a given country can be quite complex, but it’s worth noting that vos is by no means marginal. It exists in some form in a majority of Spanish-speaking countries. Some countries only use vos, some use vos as well as tú, some only use tú in writing, and so forth.

Vos in Costa Rica

So what about the Ticos? Guess what? As far as Lynnette and I have been able to decipher, it’s complicated here too!

In Costa Rica as whole, all three ways to say “you” exist

| Person | Formality | |

| tú | Second | ? |

| vos | Second | ? |

| Ud. (usted) | Third (Second meaning) | ? |

Even thought Costa Rica is a small country, there is plenty of variation in the use of second-person (you) pronouns here.

Among language nerds, the fact that vos is used in Costa Rica is kind of a meme. So we were surprised to discover that in Monteverde the use of vos seems quite limited. Here — and this seems to be a distinct pattern from the one in the capital, San José — usted has taken over almost all second person pronoun responsibilities, with nary a tu or a vos in earshot. Lynnette, who learned Salvadoran Spanish, was quite surprised to hear Costa Rican parents addressing their children with usted which would be unheard of in El Salvador. So at least for some speakers here in Monteverde, there is only one second person pronoun, usted. This pattern is sometimes called ustedeo:

“You”, Monteverde style. Just one way!

| Person | Formality | |

| Ud. (usted) | Third (Second meaning) | All formalities |

We have talked to some long-time residents of Monteverde who deny that vos plays any role in the zone. That’s clearly not the case, because, at the very least, lots of people here grew up in different areas of the country.

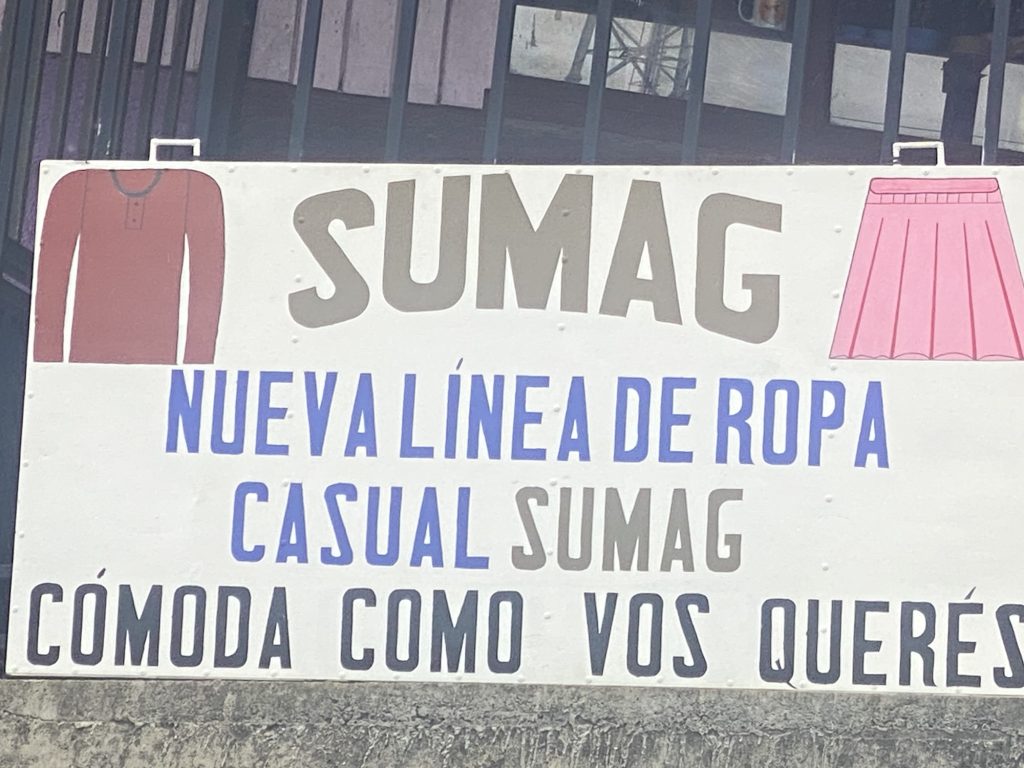

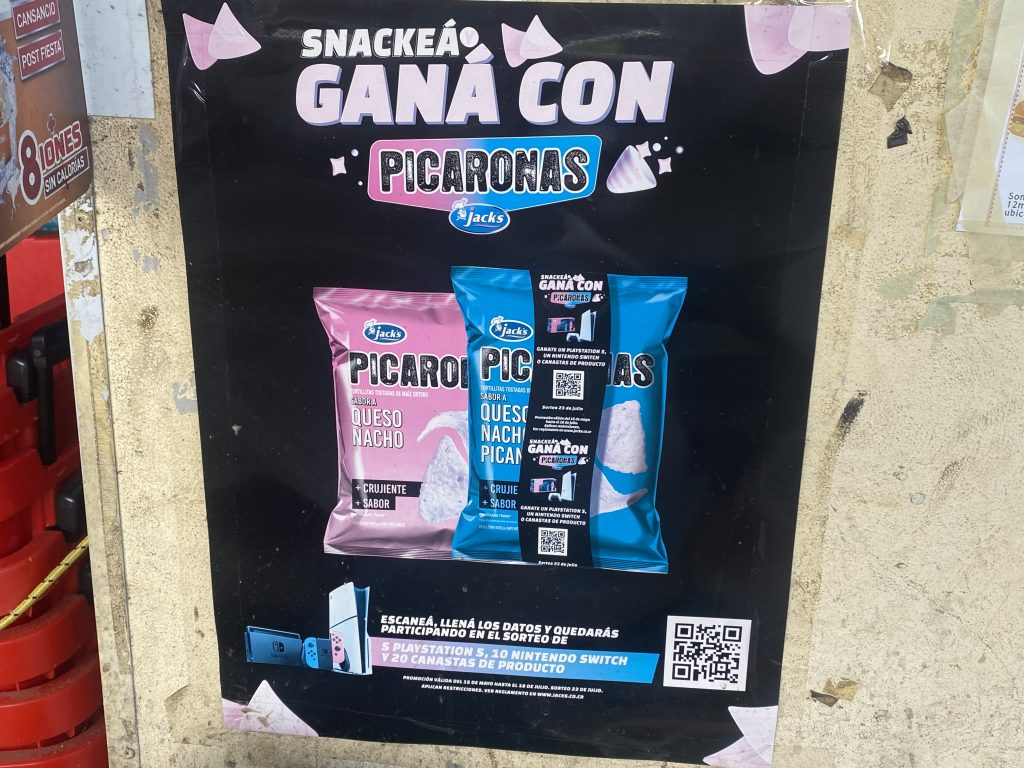

But there is one place where the evidence is plentiful: advertising.

¡y descubrí por qué con kölbi, podés más!

Recibí hasta

₡10 000 de bienvenida

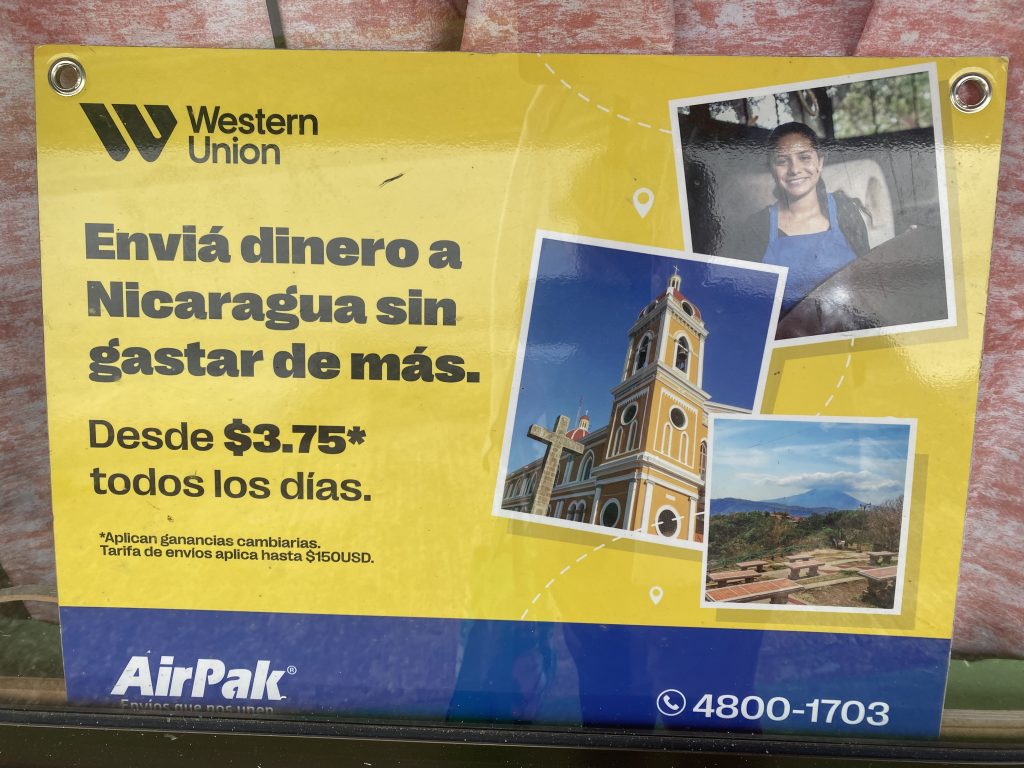

Nicaragua sin gastar de más.

Every one of these examples has verb forms that agree with vos on it, both in command (imperative) and present tense (indicative).

Transcription and translation of all the forms above

Nueva línea de ropa casual Sumag, Cómoda como vos querés.

¿Cuál querés probar hoy?

¿Tu dinero está trabajando menos que vos? Dejá que tus inversiones crezcan.

Adquirí y recargá aquí tu chip

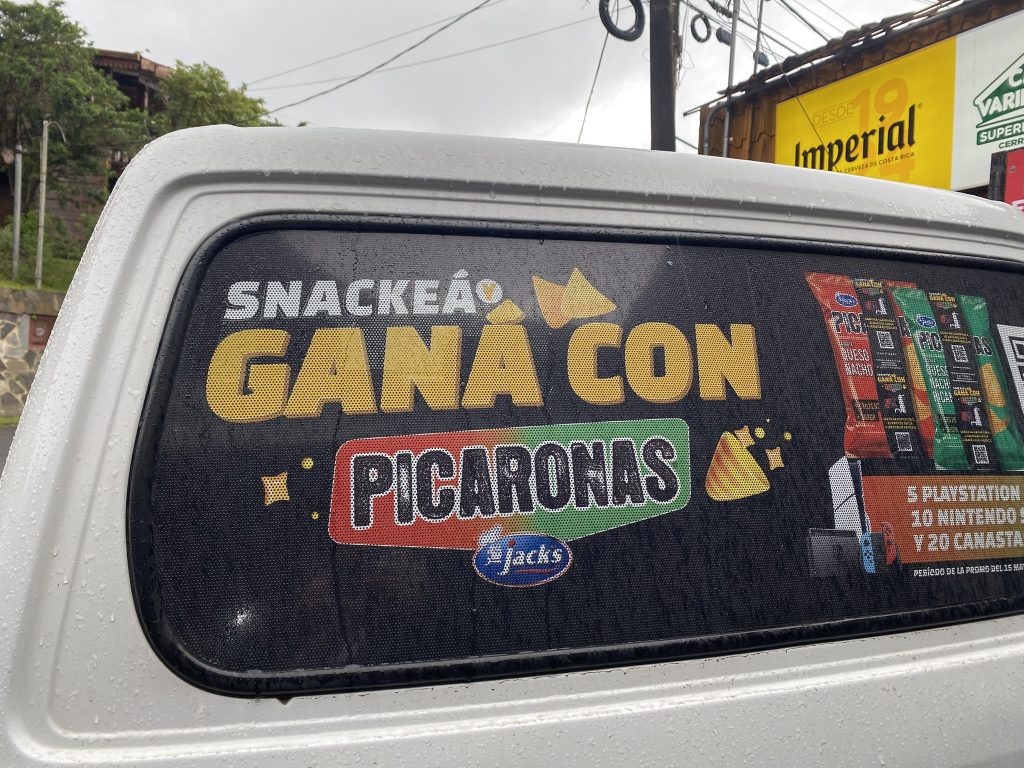

Snackeá y ganá con Picaronas

Pasate a kölbi y descubrí por qué con kölbi, podés más! Recibí hasta ₡10 000 de bienvenida

Enviá dinero a Nicaragua sin gastar de más.

Sentí el sabor

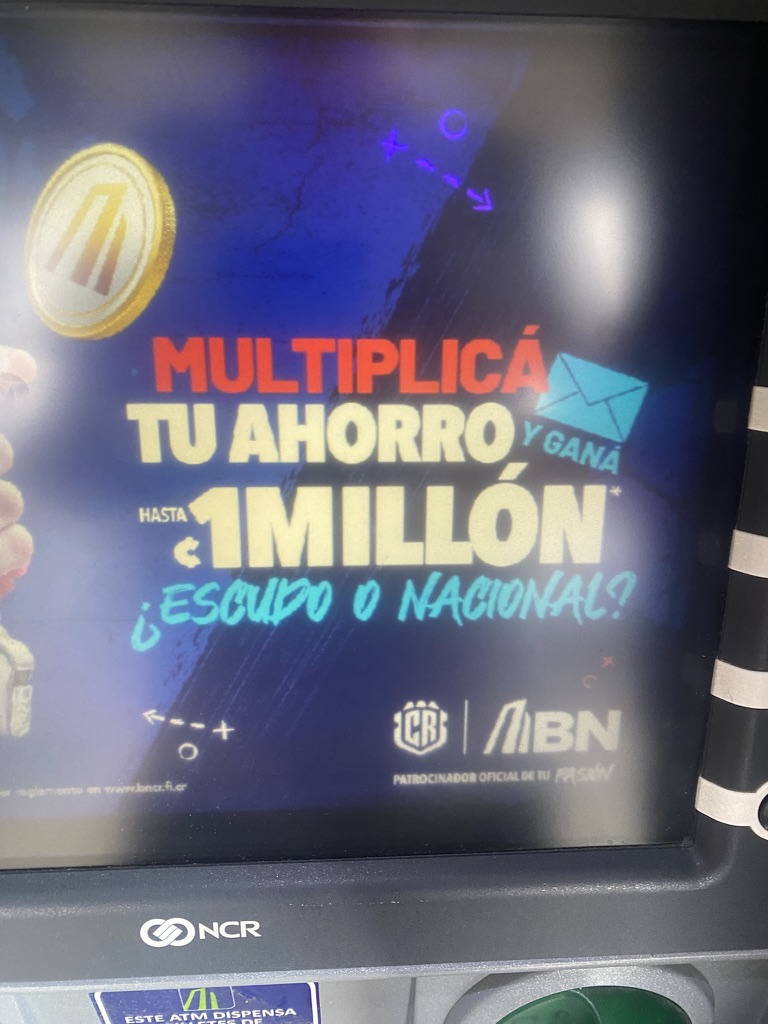

Multiplicá tu ahorro y ganá hasta

Compartí la magia de cada platillo.

GastroAlivio ¡Comprás 1 te llevás 2!

Snackeá y ganá con Picaronas “Snack and win with Picaronas!”

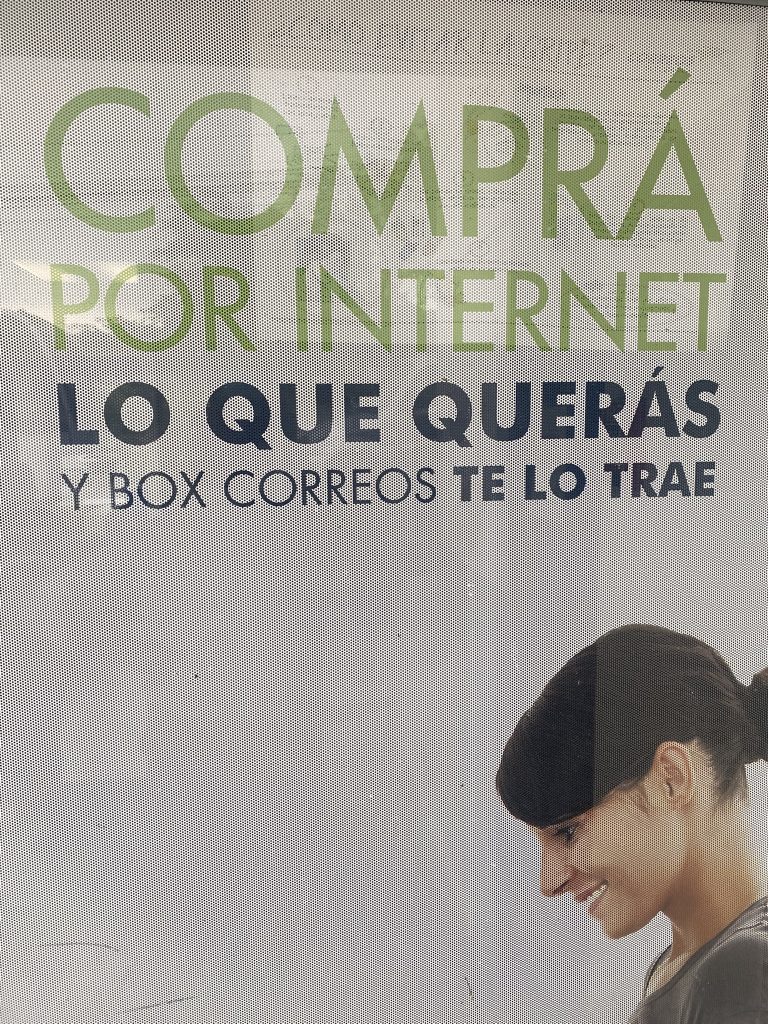

Compré por internet lo que querás

Vendé por internet lo que querás

Encendé su magia “Light your magic” by you know, drinking a beverage.

Prendé la margarita

Distrutá tu recarga al máximo

Adquirí tu SIM aquí y duplicá tu saldo

Comete un Snickers

Pausá, hidratate, y regresá con más power

Tramitá tu pasaporte o cédula de residencia

Seguí todo para tu PC

Estudiá criminología

Sonreí Todo irá sobre ruedas

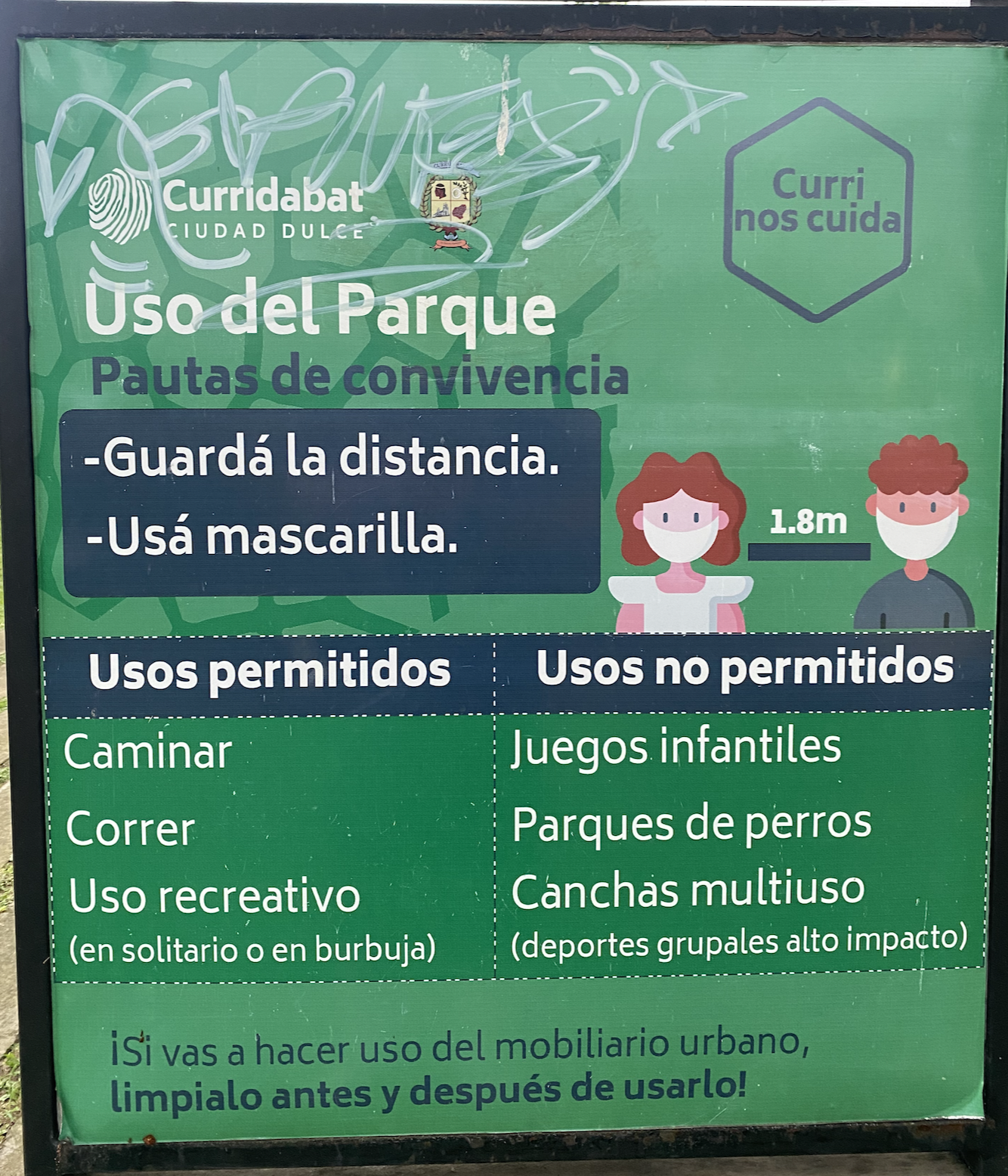

Guardá la distancia. Usá mascarilla.

What a vos form looks like

Okay, I can’t resist explaining how verbs are formed to agree withvos, mainly because it’s super simple! If you had some high school Spanish, you know the infinitive. To form the present vos form, replace the -r of the infinitive with -s, keeping the stress on the last syllable. To create the imperative, you just remove the -r, donesies.

| to speak | to light | to snack | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infinitive | hablar | encender | snackear |

| Present | hablás | encendés | snackeás |

| Imperative | hablá | encendé | snackeá |

Hablar is the simplest example, the rules are plain as day. It works the same way with encender, but it’s notable that in many other conjugations that verb is “stem-changing” — for instance, the tú form is enciendes: the e becomes ie. But stem changes coincide with stress, and since stress is final in vos forms, there’s no e to ie. Neat.

The last one just made me laugh, since it’s a borrowing from English.

Permit me, one more nerd moment: it suprised the heck out of me in my little collection above to notice a vos form in the subjunctive!

| to want | |

|---|---|

| Infinitive | querer |

| Present | querés |

| Imperative | queré |

| Subjunctive | querás |

Presumably hablés and encendás and even snackeés would be possible too.

One more example…

Okay, I’ll wrap this up already, but I have to share one more example. I have made many friends as a volunteer English teacher here in Monteverde. We met once a week for the last couple months, and it was really fun. They all work at the Mercado de Monteverde, a popular market held at the local high school. They all sell different kinds of products there. In class, we speak a fair amount of Spanish too, and I have noticed that they mostly use usted, as expected in Monteverde.

However, in a nifty video that they made to promote their Christmas event, at the very end of they video they use vos forms. I thought it was so interesting, because lo and behold, at the end of the video, there are three uses of the vos form of the verb venir, ‘to come’:

Vení a vivirlo. Come to live it!

Vení a sentirlo. Come to feel it!

Vení a ser parte. Come to be a part of it!

I asked the class about it specifically, and they said that it was a conscious decision, that using the vos form sounded more “intimate”, and more convincing.

So after all this, I’m still not sure what the deal is with vos in Monteverde! But it is certainly interesting.